The Brexit vote was never really about British foreign and security policy, except in the vaguest sense in which the United Kingdom would be free to ‘re-join the world’ after leaving the EU. Yet fast-forwarding from the June 2016 referendum to early 2020 – when the negotiations on the future relationship began – one can see that much had changed.

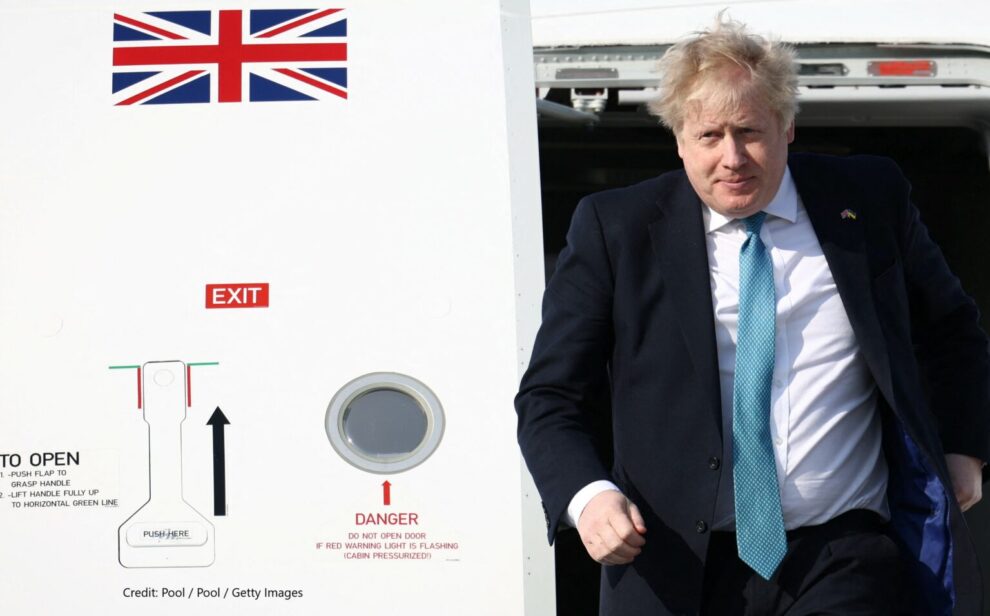

The Johnson government decided to forego negotiation on a security agreement with the EU, leading the UK to default to a ‘no deal’ outcome in this area from January 2021. Johnson also doubled down on the Global Britain rhetoric of his predecessor, Theresa May, and made much of new UK external agreements on trade and security – like the UK-Japan FTA and a series of bilateral defence agreements – as demonstrating the benefits of Brexit.

Foreign policy as compensation

Why did Brexit become a foreign and security policy issue? We argue the answer is not to be found in the internal logic of Brexit itself, but rather in the significant difference in reform costs between the economic and security domains.

The cost to the UK economy of introducing additional barriers to trade with the EU, given its geographical proximity and the intricate nature of the single market is high, and also one-sided. In contrast, the relationship in foreign and security policy is less costly to change, since the UK is one of the major strategic actors in Europe and has a host of alternative options in NATO and through bilateral ties, and since the policy area is in any case largely intergovernmental.

These conditions meant that leaders could use foreign and security policy as a means of delivering – at least in part – visions of Brexit largely unavailable in the economic domain. For those like May, seeking a ‘bespoke’ Brexit, foreign and security policy came to be seen as one of the few areas where the UK could obtain a special deal. In contrast, moving away from foreign and security cooperation with the EU allowed the Johnson government to signal a harder Brexit.

May’s proposed security agreement

May set out to deliver a bespoke Brexit that would keep the Conservative Party together by insisting on significant ‘red lines’ whilst maintaining underlying economic ties to the single market. Convinced that Britain’s vote to leave bolstered its credibility and that appeals to the individual member states could circumvent the Commission, May was wrong on both counts, and found the EU implacable on the need to avoid cherry picking, deny the UK the benefits of membership from the outside, and maintain unity at all costs.

From the moment May’s strategy was made public – months after the EU’s position had been spelled out – the government’s Brexit policy was garbed in the language of ‘Global Britain’. The slogan remained ill-defined during the remainder of May’s premiership, but it did provide the government a means to claim changes in foreign policy – and new external agreements – as benefits of Brexit, whilst also linking delivery of Brexit to the UK’s new ‘global’ identity (and not substantive change in the trading relationship).

Moreover, as the negotiations on the Withdrawal Agreement proceeded, and as the thorny Northern Ireland question brought issues of the future relationship into the conversation, it became ever clearer that May’s bespoke Brexit was unfeasible in economic terms.

In an effort to reset the negotiations and emphasise what the UK could obtain, the May government shifted focus to issues of foreign policy, with a series of major speeches on the topic, followed by proposals in mid-2018 for a comprehensive security partnership with the EU.

Johnson’s bilateralism

May’s deal ultimately failed to pass the UK Parliament as critics on the right rounded on May’s Brexit deal, labelling it ‘Brexit in Name Only’ (BRINO). In the talks on the future relationship, Johnson sought a more distant relationship through a Canada-style Free Trade Agreement (FTA). But he faced the same constraints as his predecessor in that the EU was unwilling to offer an FTA without tying the proximate UK into a stringent level playing field commitment that would reduce the UK’s capacity for regulatory divergence.

When the negotiations on the future relationship began in February 2020, the government informed the EU that the UK was no longer willing to negotiate a security agreement. The move disappointed the Commission, which found it strange the UK would depart from the Political Declaration agreed with the Johnson government in October 2019.

Observers claimed that the government’s decision owed much to the desire to demonstrate a cleaner and more autonomous Brexit in order to appease Johnson’s pro-Brexit support base, noting that security was an area where this could be easily achieved.

Johnson also doubled down on May’s Global Britain rhetoric, using it to brand major policy documents – like the Integrated Review – and sought to demonstrate new bilateral agreements and rollover trade deals as opportunities of Brexit. Moreover, the government did what it could to denigrate the EU’s role in global affairs, downgrading the status of the new EU Ambassador in London and limiting mentions of the EU in speeches and documents.

The politics of security

Both May and Johnson, in different ways, sought to use the UK’s foreign and security relationship with the EU to demonstrate the success of their Brexit policy in a way that was unviable in other domains. Because the UK has far more power in this domain, it makes sense to shift Brexit delivery – and Brexit opportunities – into this domain where possible.

This trend is unlikely to die down soon. The Labour Party’s only major speech on European policy has been on the need for a security agreement, not only because the Ukraine War has made the issue salient, but because repairing ties with the EU is far easier in this domain than is re-opening the question of Britain’s relationship to the single market. More recent Labour speeches have indeed said more about non-security issues, but without challenging the ‘red lines’ set down by the May government

Source: Ukandeu